The invention of nothing

My husband is a very important man. He is a scholar. That means he studies things. All kinds of things. He studies science, mathematics, astronomy, medicine and philosophy, as well as other things. At least, he tells me that he studies them.

To me, it seems that he spends more time sitting in a café talking to other scholars. I don’t know if they are studying or not. To me, it looks like they are chatting. But I don’t know, I’m only a woman. I look after our family, and I am not a scholar. I do not go into the café in town and spend hours talking with other men. I stay at home and look after our children and prepare food. When I am not preparing food or looking after children, I like to read books. I like to read books of adventure stories, of traveller’s tales, of poetry. I like books that make me wonder and be amazed at the world we live in. I like books that take me far away from our town and the desert on one side and the sea on the other.

We live in a town that lies between the sea on one side, the desert on the other, and a river to each side of us. They call our country Mesopotamia, the land between rivers. Because our town is a port, and because it has two rivers, there are often many people from other lands here. My husband says he meets men from India, from China, from Europe and from Africa. People from all over the world come to our town. Often they come to buy or sell things, but they also come to talk, to meet other people, to share ideas and opinions, to think about different ways of seeing the world. When a lot of people from different countries and different cultures meet, new ideas are born.

At night I lie awake on our bed thinking. “What are you thinking about?” my husband asks me. “Nothing” I reply. My husband shakes his head in despair. “Women!” he says. “They think about nothing!”

My husband often brings back books when he goes to his meetings with other scholars. He stays awake at night pretending to read them. I say “pretending” because I know he doesn’t read them really. Sometimes I go in to his study late at night and I find him asleep, snoring with a book open in front of him. When I wake him up he says how interesting the book he’s reading is. I ask him to explain it to me, to tell me about it, but he says that women don’t understand such things. I let him go back to sleep and take the books for myself.

Some of them are very interesting. There are collections of stories from all around the world. They make me think. They make me think about lots of things. And the books about arithmetic from Greece and India, and the books about astronomy and navigation from Europe and Africa, they make me think about nothing.

“How many numbers are there?” I ask my husband. He likes it when I ask him questions. It makes him feel wise and intelligent.

“Nine hundred and ninety nine thousand nine hundred and ninety nine” he answers.

“And if I add one more?”

“Then the world will end” he says. I don’t believe him.

“How many stars are there?” I ask him. He doesn’t know. “Where does the land end and the sky begin?”, “What happens if a ship sails until the end of the sea?”

My husband can’t answer any of my questions. He thinks I’m stupid because I ask them.

“Is ‘nothing’ a number?”

“Of course it isn’t!!” he replies. “How can ‘nothing’ be a number? If a merchant has five horses, then he sells five horses, how many horses does he have?”

“No horses, but lots of money.”

“If I buy ten aubergines from the market, then I eat ten aubergines, what do I have?”

“A fat stomach”.

We laugh. He thinks I’m stupid.

His answers are right if we only think of merchants, traders, salesmen and market people. His answers are right as long as we think of money and buying things and eating things. I understand this. But when I read the books about philosophy that he brings back from his meetings, I think that there is more than this. I think that the world cannot be explained in terms of buying and selling things. We cannot describe the world as if it were only a huge market.

“Nothing” is not a number that is good for people who buy and sell things. But if you want to be a navigator, if you want to travel and discover other countries, if you need to know where the sea ends and the sky begins, you need different numbers.

I am helping my children to learn. We practise counting. We count all our fingers, then our toes too. Five fingers on each hand. Ten fingers altogether. Five toes on each foot. Ten toes altogether. “What comes next?” asks my son. “What comes after ten fingers and ten toes?”

“Then you have to start again!” I tell them. My son hides all his fingers and makes a fist. “How many fingers?” he asks me.

“None!” I reply.

But how can “none” or “nothing” be “something”?

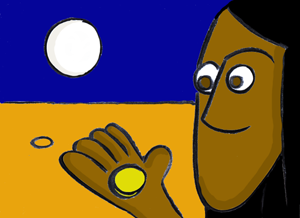

At night, when it’s cool I walk out into the desert because I like to be alone. I draw numbers in the sand. I draw a line for “one”, two lines for “two”, three for “three”…and for “nothing”? What should I draw for “nothing”?

I put a coin down in the sand, then I remove it. It leaves a small, empty circle in the sand. This is it – sifr, empty. Zero.

My sign looks like a plate after someone has eaten all the food. It looks like a cage when all the animals have gone. It looks like a sack with all the grain taken from it. It is nothing, and it is also something.

I write down my symbol on paper. I write down an explanation of what it means. I write down why it will be useful to geographers, mapmakers, travellers, astronomists, navigators, scientists, philosophers and poets. I put the piece of paper in one of the books my husband takes back to his meetings in the café.

The next day, my husband comes back from his meeting at the café looking very happy. He tells me that he has just made an important discovery. Some of the other men in the café were very interested in the piece of paper in the book. He will probably become famous, he tells me, rich and famous. “History will remember me as a great mathematician.”

I go out into the desert at night again. I try to count all the stars in the sky. I can’t decide how many there are, and what number could ever possibly describe them.

I will be ignored by the important men in the café meetings. I will be forgotten by history. Perhaps that was because I invented something. I invented nothing.